Figure 1: An image showing a series of African women carrying water on their heads (Source: Women eNews Kenya 2011)

Water is essential to achieving

gender equality. In recent years, gender equality has come into focus in global

policy, for example, the United Nations (UN) is calling for gender equality by

2030. Further, in 2010, the UN recognised the human right to water and

sanitation (UNDESA 2014). In Africa, many countries are

codifying these rights. For example, in Malawi, the 2013 Water Resources Act

and the Gender Equality Act recognise the right to water as well as gender

equality (Hellum et al. 2015: 2). Despite an increased

level of codification, many states fail to fulfil these rights for their

residents. In 2017, 22% of Malawians did not have basic access to an improved

water source within 30 minutes of the home (Cassivi 2020: 788).

As I explored in my previous

blog, women disproportionately carry the burden of government failures in water

provision. The gendered division of water labour means that, inherently, the

right to water is a prerequisite for gender equality in all facets of life (Hellum et al. 2015: 3). This is because freeing

up labour time through adequate water provisioning can have a ‘ripple effect’

for women’s empowerment by giving them time to go to school and participate in

economic activities (Bah 1988: 98).

The importance of water to

women’s rights extends beyond water collection. Water and sanitation are two

highly entangled concepts. Water is a prerequisite for adequate sanitation

facilities. Although significant improvements have been made in access to

sanitation over the last 20 years (Figure 2), in 2017, 701 million people

across the globe relied on unimproved sanitation facilities (WHO-UNICEF JMP 2019: 8). Sub-Saharan Africa lags

behind the rest of the world in terms of coverage of basic sanitation services

(Figure 3) and also experiences some of the highest rates of open defecation

(Figure 4).

Figure 3: A map showing global sanitation coverage (Source:JMP WHO-UNICEF 2019: 30)

Figure 4: A map showing rates of open defecation (Source: JMP WHO-UNICEF 2019: 14)

Women have unique sanitation

needs, including, menstrual hygiene management, therefore, a lack of sanitation

facilities disproportionately affects women (Corburn and Hildebrand 2015: 1). In Africa, many

women lack access to safe and clean sanitation facilities (Figure 5).

Without access to menstrual

health management materials, a period can interfere with everyday activities.

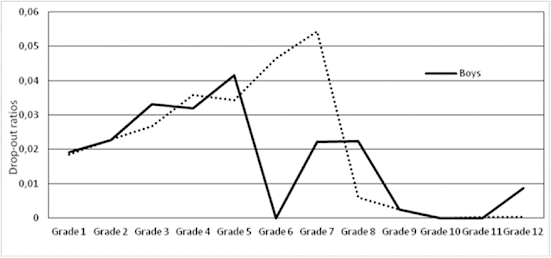

This is particularly relevant to education outcomes. One study in Zambia noted

that the majority of those who drop out of school between grades 5 and 7 (the

time when menstruation usually begins) without water or sanitation access at

home were girls (Figure 6) (Agol and Harvey 2018: 289).

Figure 6: A chart showing drop out rates according to gender and grade (Source: Agol and Harvey 2018: 289).

This is opposed to ‘no

significant gender difference’ amongst children with water and sanitation

access at home (Agol and Harvey 2018: 289). Whilst this

relationship is disputed on account of other factors that might be responsible

for drop-out rates, such as participation in the economy, this study still

presents a logical argument supported by statistically significant results.

Addressing barriers to women’s

education is not only important to gender equality in terms of educational

outcomes, but can also precipitate improvements in women’s quality of life more

broadly. For example, increased women’s education has been proven to be linked

reduced maternal mortality (Karlsen et al. 2011: 1).

Clearly, the provision of

adequate water and sanitation facilities is essential to addressing women’s

needs and achieving a gender equitable future in Africa.

What an interesting read! I thoroughly enjoyed reading this blog, and appreciated how you included multiple graphs and figures to back up your argument. Figure 2 in particular was very powerful as it clearly showed the spatial distribution of the world's proportion of population using at least basic sanitation services. You stated that many African countries are beginning to codify the human rights to water and sanitation but many states still fail to fulfil these rights to residents. Why do you think this is, and do you think in the future we will see any improvement for women's rights to water?

ReplyDeleteThank you for your comment Kavitri! I also really liked the maps I found in the JMP report, as they really brought the story to light for me. Access to sanitation does not have a quick fix, it’s a multi-faceted issue which will require vast amounts of funding as well as local consultations so the situation is unlikely to improve overnight. In addition to this, I personally believe there is a need to move away from Eurocentric standards surrounding the bathroom that are perpetuated by development agencies and charities. The Western flushable toilet we are familiar with is highly water intensive and this means that it is not necessary suited to water scarce environments. Therefore, innovation is needed to create sanitation solutions that are context-appropriate in Africa.

DeleteBetween 2000 and 2020 500 million people in Africa gained access to basic drinking water and 290 million people gained access to basic sanitation. This pace of improvement is not fast enough to achieve universal access to safely managed drinking water, sanitation and basic hygiene services by 2030, however, it is progress nonetheless. It provides me with hope that women will, at some point in the future, achieve equitable access to water. When it comes to women’s access to water, I see dismantling gender norms that encourage women to drink last and least as fundamental to the endeavour to establish gender-equitable water resource distribution. Legally codifying women’s rights to water may be one means through which this can be achieved.

here is the link to the source of the statistics I cited: https://www.unicef.org/senegal/en/press-releases/africa-drastically-accelerate-progress-water-sanitation-and-hygiene-report#:~:text=About%20500%20million%20people%20gained,hosted%20by%20the%20African%20Ministers'

Delete